GP Skin in the Game

1,503 funds and 20 years of data point to the GP commitment sweet spot 📍(spoiler: more isn’t always better)

Earlier this year, one of my school-aged kids came to me with what he thought was a brilliant idea. A diehard football fan, he felt very confident about the outcome of an upcoming game. His pitch? I place the bet with my money. If he’s right, we split the winnings 50/50. If he’s wrong, I eat the loss.

Needless to say, I passed (you would’ve too).

And no, not just because sports betting is illegal. But because what he was proposing is a textbook example of misaligned incentives. The kid was attempting the oldest trick in the book: using OPM (other people’s money) with no skin in the game.

Which brings us to private placements, where the same principle applies. When General Partners (GPs) invest their own capital alongside Limited Partners (LPs), it serves as a critical alignment mechanism.

Real money on the line = the GP believes in the strategy and is willing to bet on it (and not just with his mom’s dollars).

The data backs this up. Multiple studies show a clear pattern: fund performance improves when GPs have meaningful skin in the game. But there’s a catch: the benefit plateaus (and then diminishes) beyond a certain point.

Of course, no conversation about skin in the game would be complete without discussing the ways to sell the stakes:

So what does real “skin in the game” look like? In this post, we’ll discuss:

✅ Typical co-investment ranges

✅ What the data suggests is the optimal range

✅ Why a stated GP commitment isn’t always real skin in the game - and how tying up too much of a GP’s net worth can create its own risks.

✅ What LPs should actually look for when evaluating GP alignment

On a somewhat related note, info on fees in REPE:

📚 You’ll find all sources and additional reading material at the end of the post.

Typical Ranges of GP Co-Investment

This is one of the most sensitive (and contentious!) topics you can raise with a GP. Especially one who’s just starting out and doesn’t have much liquid capital to commit. Ironically, those are often the very GPs who have the strongest incentive to chase higher-risk deals with the potential for big returns.

Yes, reputation is always on the line. And yes, in real estate private equity, GPs often take on additional exposure through recourse loans. But there’s no substitute for personal capital: when your own money is at risk, the decision-making changes (generally, for the better).

🧮 So how much money are we talking about?

The challenge is, we only have reliable data from the institutional end of the spectrum (funds large enough to report to third-party databases). Below that line, it’s the Wild West. I’ve seen GP commitments range anywhere from zero to 20% of the fund.

For newer GPs, the best path may be to focus on smaller deals or pursue opportunities with quicker turnaround times (which would enable them to earn the promote and recycle it into larger transactions).

Between 2018 and 2023, some GPs scaled rapidly without contributing any of their own capital to the deals they syndicated. Money was easy, and FOMO was rampant. But I can’t help but wonder: could some of this have been avoided if more LPs had insisted on greater GP co-investment? (among other things)

Back to funds we have data on:

For a long time, the industry norm for skin in the game hovered around 1%. It was often viewed as a symbolic gesture rather than a substantial personal stake. However, times are changing, and LPs are demanding more genuine alignment.

Recent data reveals a clear upward trend:

A 2018 report by MJ Hudson indicated that 2-2.99% had become the most common range, with a growing number of funds seeing commitments in the 3-4.99% bracket.

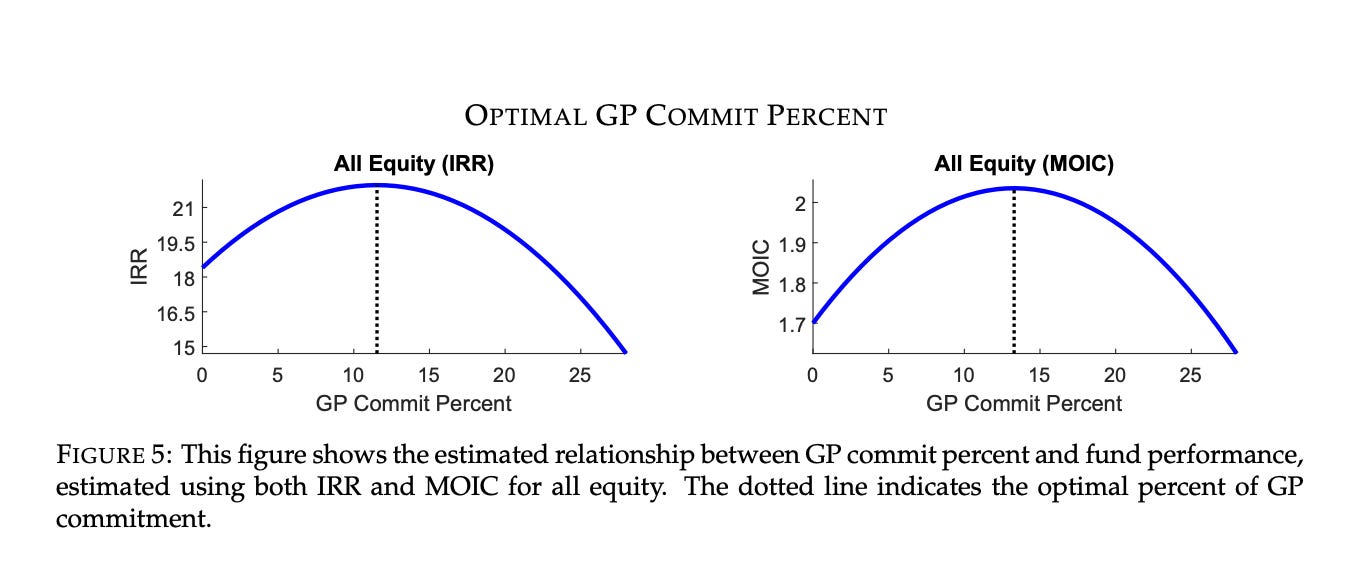

More recent academic research found the average GP commitment across 1,503 private equity funds (1994-2019 vintages) to be 3.5%, with a median of 2.0%.

📌Notably, this study suggests an optimal range for fund performance to be between 10-13% of committed capital, significantly higher than the current average.

How LPs Can Evaluate GP Commitment

But a headline percentage doesn’t tell the whole story. The quality and structure of a GP’s commitment matter just as much as the amount. ILPA emphasizes that GP contributions should be “substantial cash contributions,” and that restrictions should exist around transferring those interests.

📌 Questions LPs Should Be Asking:

Cash vs. carried interest waivers:

Is the GP’s commitment actual cash from their own balance sheet, or just a reduction in fees or future carry? Imputed capital contributions may look good on paper, but LPs overwhelmingly prefer cold, hard cash.Cash vs. fees:

In REPE, it’s not uncommon to see acquisition fees re-characterized as GP commitment. That’s LPs paying for the GP’s “skin in the game.” Draw your own conclusions please.Direct vs. indirect:

With larger funds, is the capital coming straight from the pockets of key principals, or from the management company? The closer the money is to the decision-makers, the stronger the alignment.Direct vs. “Friends and Family”:

Some institutional JVs require 10% co-invest, but allow it to be filled via friends and family capital. Make no mistake, if the GP isn’t personally exposed, there’s little deterrent to taking outsized risks.“Cherry-picking”:

Can the GP opt in or out of specific deals, or are they required to invest across the full portfolio?Proportionate responsibility:

Are all senior investment professionals contributing meaningful amounts, in line with their role and compensation? If not, who’s really bearing the risk?

Is More Better?

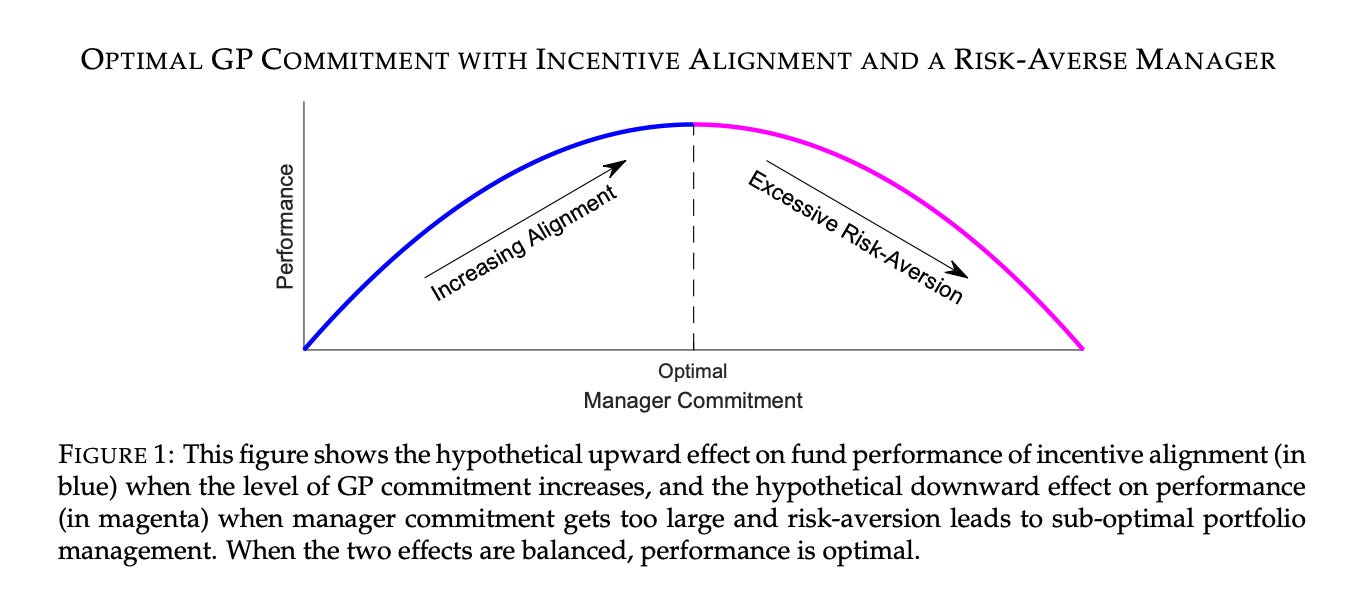

While GP commitment is intended to foster alignment, both insufficient and excessive "skin in the game" can introduce their own set of conflicts.

Under-investment (too little skin): When a GP's capital stake is minimal, the incentive for hyper-vigilance might diminish. Below an optimal range, lower GP commitment correlates with sub-optimal fund performance. This could lead to a classic moral hazard problem.

If the GP stands to lose little, they might:

be less rigorous in their due diligence processes, taking on riskier investments with LP capital.

prioritize other ventures or personal interests over the fund's success.

be more inclined to take outsized risks with the fund's capital, knowing their personal exposure is limited, thus shifting the downside to LPs.

Over-investment (Too Much Skin): this will seem counterintuitive, but an overly large GP commitment can also create conflicts. Research indicates that beyond an optimal range (e.g., 11-14% GP ownership), "investment behavior becomes more conservative" and "GPs with more skin in the game make safer bets." This can manifest as:

Risk aversion: GPs may become overly cautious, shying away from potentially high-return but riskier deals that might otherwise fit the fund's strategy. Their personal wealth is heavily tied to the fund, leading to a fear of losses.

Concentration risk for the GP: if too much of a GP's personal net worth is tied to a single fund, it could create undue pressure to make decisions that prioritize their own liquidity or wealth preservation over the fund's long-term, illiquid strategy.

LPs, Make Your Preferences Heard

The trajectory of GP commitments is unmistakably upward. What was once a token 1% is now commonly 3-5%, with top-tier funds sometimes seeing double-digit commitments from their GPs.

As an LP, you have every right to expect stronger alignment. Learn to understand the nuances of GP commitment (amount, structure), and be aware of the potential pitfalls of both under- and over-investment. While your voice may not move the needle with a $15 billion fund, it absolutely should with a $250 million manager. Remember, you always have the power to vote with your dollars: fees and structures vary widely.

New Here?

You’ll find more articles on the following topics:

📚 Further Reading

Do GP Commitments Matter?

Institute for Private Capital, UNC Kenan-Flagler Business School

Excellent report with the most recent data on GP commitments."Skin in the Game: General Partner Capital Commitment, Investment Behavior and Venture Capital Fund Performance"

CFA Institute, 2018

Earlier article with data cited in the UNC report above. Offers a look at how GP capital commitments influence fund behavior and outcomes.ILPA Principles 3.0

Institutional Limited Partners Association

A foundational resource outlining best practices for alignment between LPs and GPs. Institutional LPs are guided by this—retail LPs still have catching up to do.Understanding General Partner (GP) Stakes Investing

GLASfunds, 2024

A solid overview of GP stakes investing and its growing appeal among institutional investors.GPs Are Making Larger Fund Commitments—Just Not for the Reason You Think

Institutional Investor

Explores the recent trend of increased GP commitments and the motivations behind them.

As a new subscriber, I have enjoyed reading your work. However, this post rubbed me raw. As a GP perhaps I might offer a different perspective. Rather than evaluate the GP’s contribution as a % of the capital stack, try evaluating as a % of the GP’s liquidity and net worth. You might find the GP is “all in” even though they don’t have a trust fund to allow them to invest at an “ideal” level. Further, I can honestly say that my effort towards a deal has never been influenced by a couple % more or less of capital that I’ve put in, and further the idea that I would treat F&F is worth less than my own is simply offensive. At the end of the day, people do business with people and trying to quantify an ideal GP based on an average, I believe, is a flawed analysis. I’m not an average GP regardless of my skin in the game.

This is a great and much needed post. I like to ask the non CEO employees how much they and their families invest in every deal and if not why?