Imaginary Gains, Real Fees

🧮 How private funds turn paper profits into real fees (and why LPs need to read page 763 of the prospectus)

Happy Sunday!

Today’s case study is a bit unusual. It’s a totally fictional and wildly exaggerated secondary fund. CRE folks, don’t zone out just yet: NAV-based evergreen CRE vehicles are closer cousins to these than you think.

What inspired the case study is this Wall Street Journal article by Jason Zweig. I shared a simple analogy that caught fire on X/Twitter:

🍳 How the Sausage Is Made

Many of you and asked the same, excellent question:

“HOW THE HECK do they pay a promote if the assets aren’t sold?”

And since you would rather stab yourself with a fork than dive into the intricacies of GAAP statements, I thought I’d run with my analogy, and explain things in a simple fashion.

Here’s a deep dive into Hamilton Lane’s Private Assets Fund, the one that inspired the WSJ article:

This is for educational purposes only—not financial advice. Numbers and details are purely fictional and hypothetical. Not a solicitation. Not a fund. Don’t ask me the sponsor’s name, fund already over-subscribed.

The Pitch

Awesome Secondary Fund buys private assets in the secondary market. Someone invested in these assets a few years ago, but now wants out. Awesome Fund steps in, negotiates a discount, and buys the stake.

Here’s a primer on how secondary funds work:

To get started, Awesome Fund lines up some purchases and finds a seed investor who buys 50,000 shares at $10 each. Total capital raised: $500,000.

(By the way, this fund is doubly awesome: no leverage, no depreciation. Otherwise, you’d be reading a 10,000-word accounting essay on a Sunday - ain’t no one got time for that. You’re welcome).

The Life of the Fund

The manager finds an amazing asset with a sticker price of $500,000, negotiates a 10% discount, and buys it for $450,000.

IMPORTANT: how do we value this asset?

Well, if you slept through econ, let me refresh you:

Fair market value is “the price at which an asset would change hands between a willing buyer and a willing seller, both having reasonable knowledge of the relevant facts, neither being under any compulsion to buy or sell, and both acting in their own best interest.”

By that logic, Awesome Fund should just record the asset at $450,000, the price it paid.

But that’s not what happens.

Because these assets are thinly traded and hard to price objectively, the fund goes ahead and marks it up to $500,000 (the original “sticker price”). Totally legal, by the way. (Happens quite a bit in the real world, believe it or not).

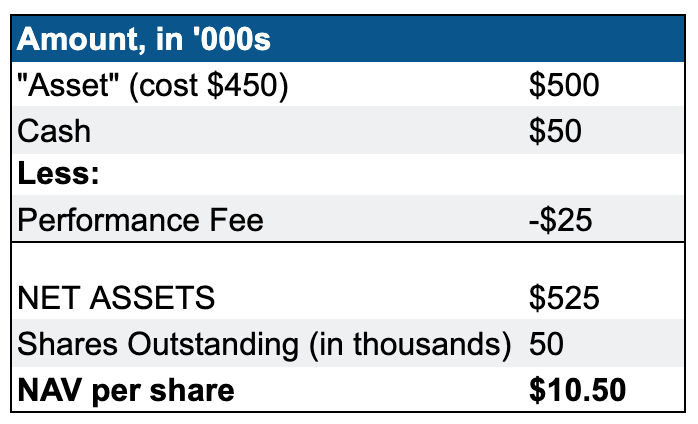

Now the balance sheet shows:

$500,000 “asset” (including $50,000 unrealized gain)

$50,000 in cash.

💸 Fund Manager Compensation

Back to Zweig’s point: Hamilton Lane earns performance fees on unrealized gains.

Awesome Fund - not to be outdone - does the same.

Side note: we can have a good long discussion on the messed up incentives this creates - but that’s a topic for another day.

The fund manager crystallizes a $25,000 performance fee (assume a 50/50 promote). This performance fee is earned before the asset is sold.

Here’s what the balance sheet looks like. Note what it did to NAV per share, even after the performance fee was paid:

🤔 Where’s the Cash Coming From?

If you are still with me, you are dying to know: where’s that $25K the GP pays themselves coming from?