Private Equity 101: What Every LP Should Know

The basics of fund mechanics, performance dispersion, and why transparency still lags.

Private equity has long carried an aura of exclusivity and legendary returns. For decades, it was the domain of elite institutions and the ultra-wealthy. Just getting in the door often required a seven-figure check and a warm introduction. (This has to explain why so many people are so enamored with the asset class, but I digress.)

That’s changing.

Access has broadened through feeder funds, digital platforms, and the expanding “wealth channel.” The industry has fought hard to “democratize” private equity, and the day may soon come when you’ll see it as an option in your 401(k).

That’s the good news.

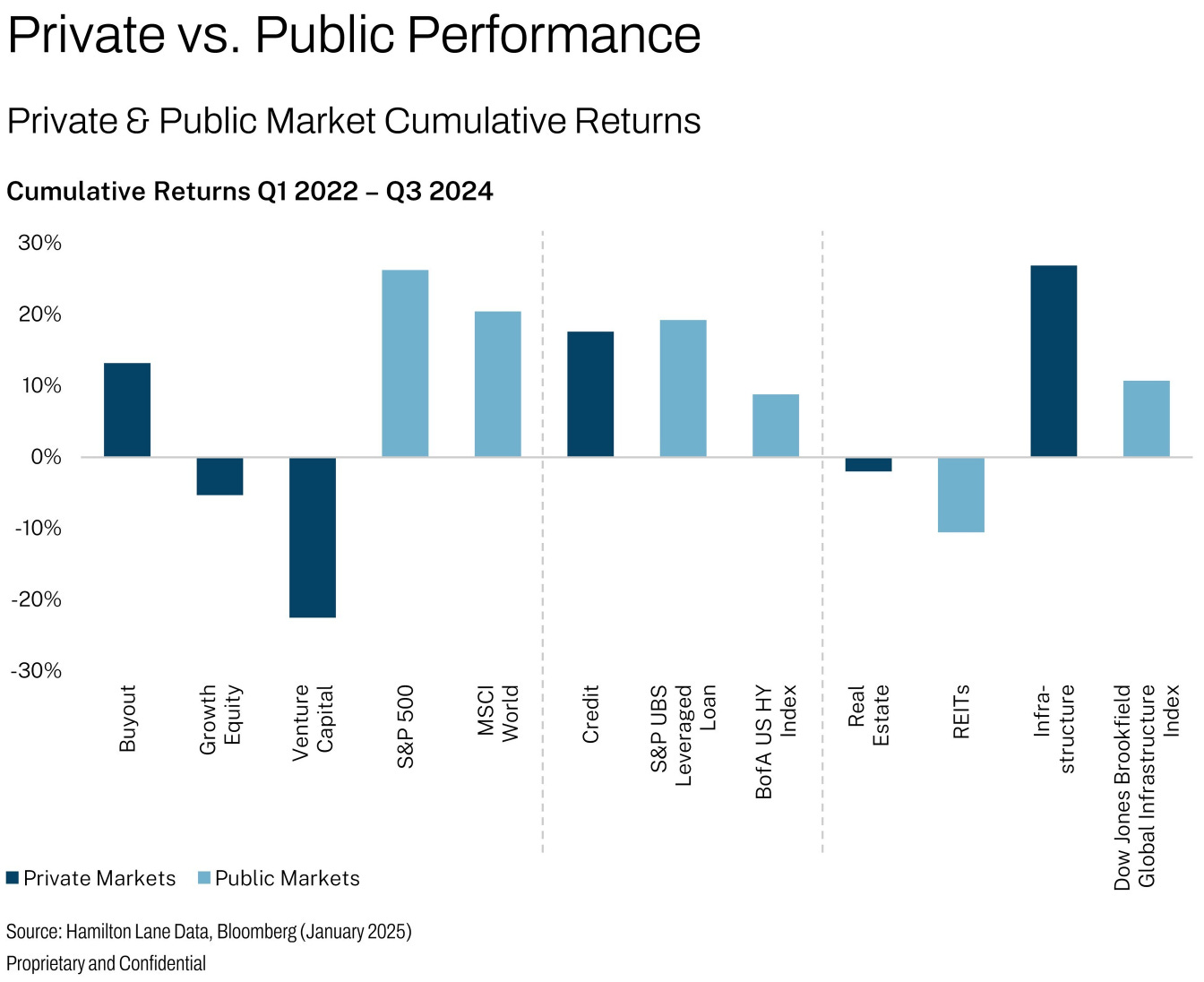

The bad news? Access has been democratized, but transparency hasn’t. And increasingly, the returns don’t live up to the legends passed around in business school hallways - on average. (But the top quartile still outperforms by a wide margin.)

I wrote about the slow death of illiquidity premium here:

Today, we’ll walk through the fundamentals of investing in private equity funds and talk about what LPs should watch for in fund structure, strategy, and incentives.

We’ll cover:

How private equity funds are structured

What investors should know about fees, fund terms, and performance mechanics

Red (and yellow) flags LPs often overlook

You’ll also find a set of starter questions to use in due diligence.

This post explores the data behind performance persistence: how often top-performing managers actually stay on top.

What Is Private Equity and How Does It Actually Work?

You all know this, but very briefly. Private equity (PE) is an asset class where General Partners (GPs) raise capital from investors (LPs) to acquire, grow, and eventually sell private businesses (known as portfolio companies).

GPs typically purchase majority stakes in mature, cash-flowing companies using a mix of investor equity and debt. (This is where private credit comes into play—many of these acquisitions are funded by private lenders.)

The goal: create value, improve operations, and generate profits at exit.

PE vs. Venture Capital

Keep this in mind:

While both invest in private companies, PE funds focus on later-stage businesses with established revenues. Venture capital (VC), by contrast, targets early-stage startups. The strategies, time horizons, and risk profiles are worlds apart (VC being much higher on the risk scale).

GPs Are Active Owners

GPs are active owners: they acquire, restructure, grow, and eventually exit their investments. How?

Replacing or upgrading management

Driving cost efficiencies

Consolidating smaller players

Expanding margins

The best GPs have a repeatable playbook, one they’ve executed across multiple funds.

Read this on performance persistence:

📌 For LPs: Historical headline returns don’t tell the entire story. During due diligence, it’s important to focus on whether the GP can still execute operational improvements in today’s environment, where multiple expansion and cheap debt aren’t doing the heavy lifting anymore.

How PE Funds Are Structured

When a GP launches a new fund, it raises capital commitments from LPs over a one- to two-year fundraising period. Once fundraising closes, capital is drawn down gradually, typically over a five-year investment period, as the GP identifies and acquires portfolio companies.

Deals may include:

Full acquisitions (a.k.a. leveraged buyouts or LBOs)

Carve-outs from larger companies

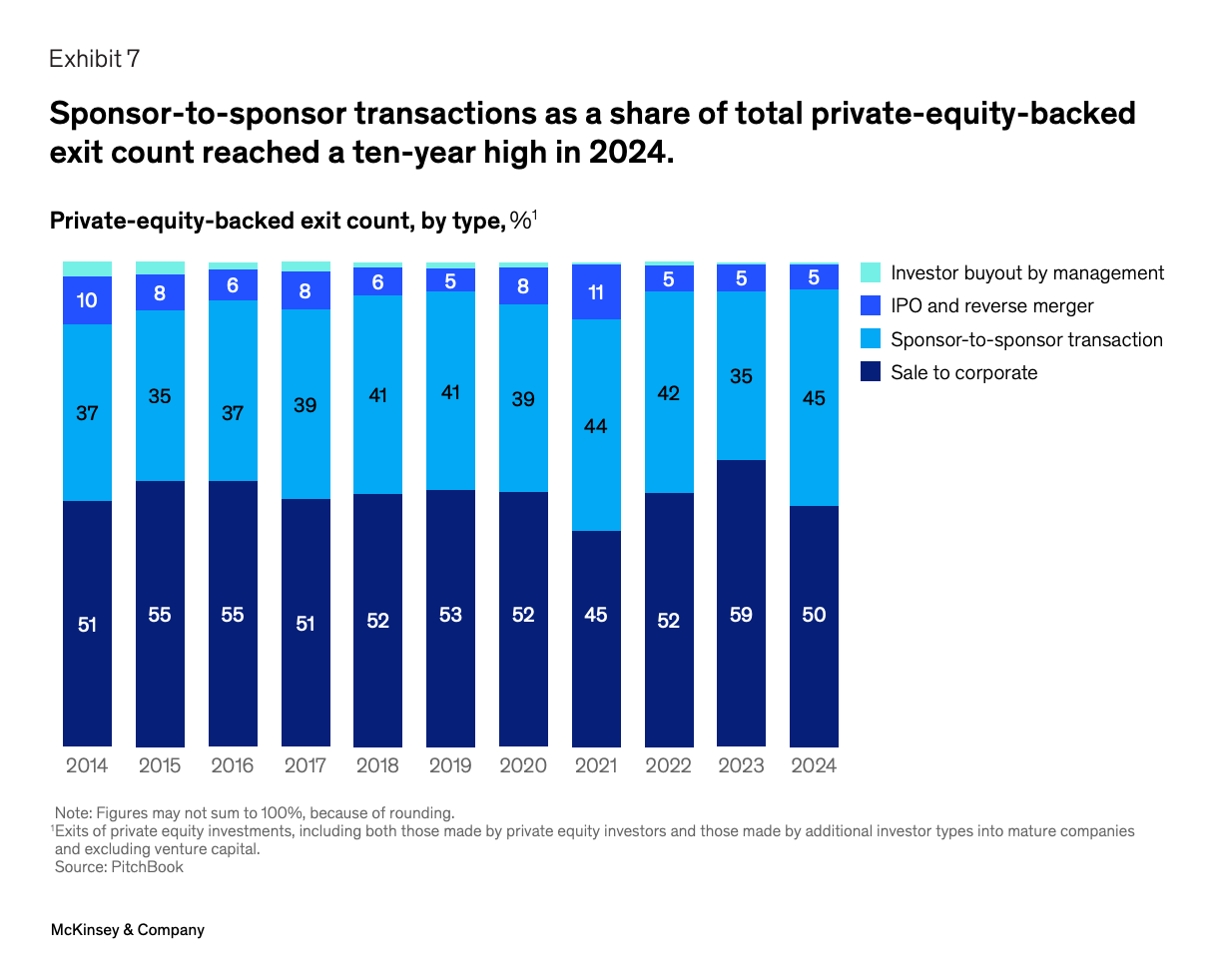

Sales between PE firms (known as secondary buyouts)

⚠️ Secondary buyouts used to be viewed as red flags. It’s not as black-and-white as that, however. These transactions could reflect increasing specialization. One firm might focus on cost-cutting; another might be a platform-builder focused on roll-ups.

📌 As an LP, don’t assume a secondary deal is a problem. But do ask:

What’s the strategic rationale?

What capabilities is the next GP bringing to the table?

Most importantly—what’s the valuation, and how is it calculated?

The Fund Lifecycle

Private equity funds typically span about 10 years, moving through three overlapping phases:

1. Fundraising (Years 0–2)

LPs commit capital, but no cash changes hands yet.

2. Investment (Years 1–5)

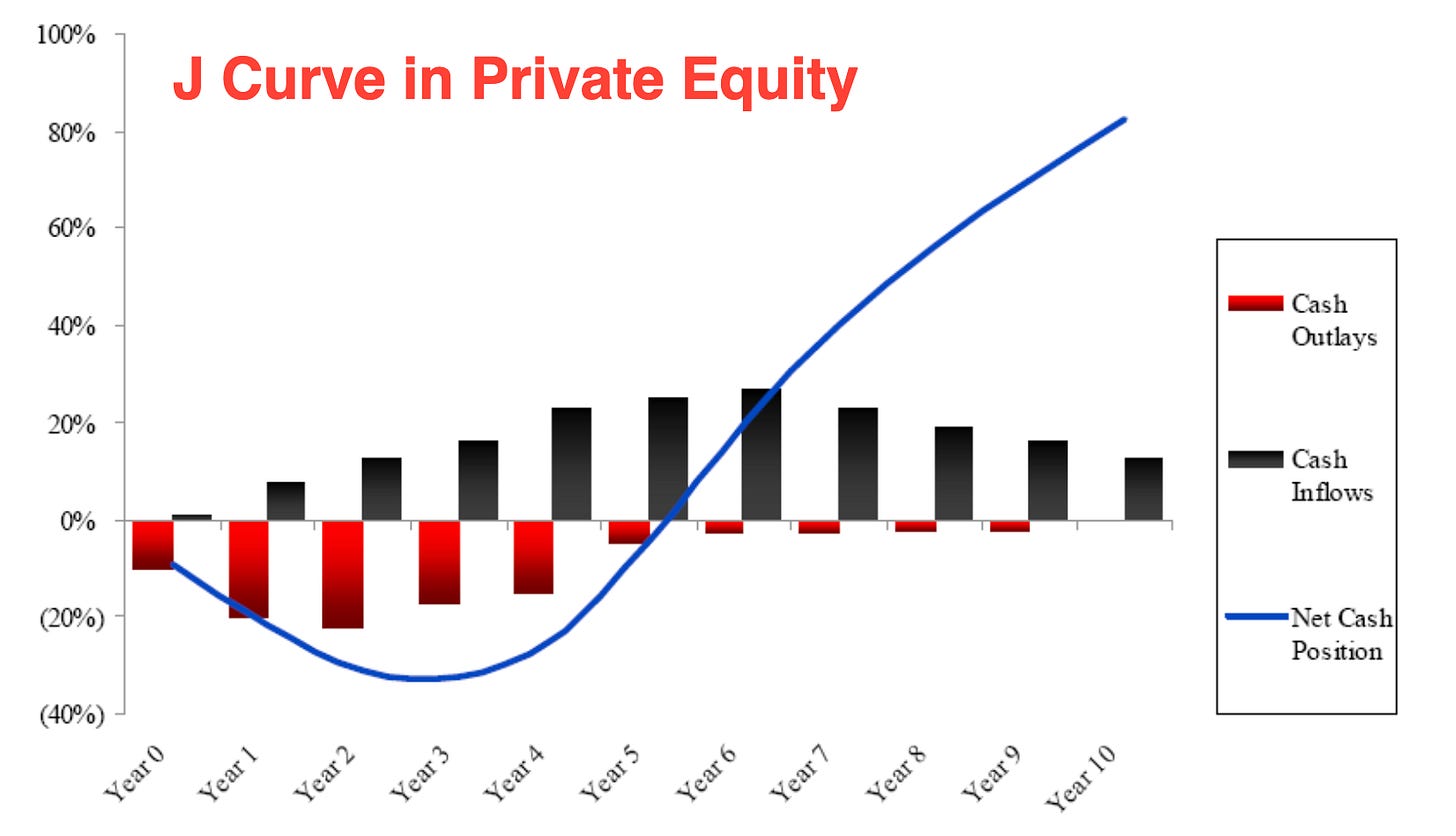

Capital is drawn down in tranches as the GP assembles a portfolio. These “capital calls” can come with short notice, which creates what’s known as cash drag—LPs must keep liquid reserves ready to deploy.

3. Harvesting (Years 4–10)

As companies are sold, proceeds are returned to LPs.

Returns don’t come in steadily: they’re lumpy because not all portfolio companies are sold at once. Most funds follow a “J-curve” pattern: returns dip early due to fees and unrealized investments, then rise later when exits occur.

That’s why institutional LPs typically commit across multiple funds and vintage years. This is done to smooth out cash flows and reduce timing risk.

Fund Structures, Fees, and Incentives

In theory, private equity fund structures are designed to align the interests of General Partners (GPs) and Limited Partners (LPs). In practice, it’s not always the case.

Retail investors often can’t negotiate fund terms, but they can vote with their dollars. Understanding how fees, carried interest, and profit-sharing mechanics work is critical (also, this is about the only transparent thing about blind PE funds).

GPs need fees to pay overhead and remain in business. But for LPs, fees eat into returns - and must be taken into account when considering allocations.

(Are fees the most important thing? Absolutely no.)

For more on incentives, read this:

The “2 and 20” Model Is Dying

The classic private equity fee structure, known as “2 and 20”, includes:

2% annual management fee, and

20% carried interest (i.e., the GP’s share of profits after a minimum return is hit)

This model was designed to fund operations, attract talent, and reward performance. But in today’s market, it’s increasingly under pressure, especially in larger funds.

🧮 Do the math:

A flat 2% fee over a 10-year fund life can consume 20% of committed capital. That’s before any carry is paid out. Since fees are usually based on committed (not invested) capital, they eat into LP returns early, contributing to the infamous “J-curve.”

Institutional LPs now push for lower fees, especially in mega-funds. Many newer or smaller funds charge 1–1.5% instead.

📌 What LPs should watch:

Is the fee based on committed or invested capital?

Are there step-downs in later years?

Is the fee aligned with actual operating costs?

Carried Interest (a.k.a. “Carry”, a.k.a. “Promote”)

Carried interest—typically 20% of fund profits above a hurdle rate (often 8%) is meant to align GP compensation with LP performance. In theory, it’s a performance-based reward. But the details matter.

⚠️ One key issue: carry is often tied to IRR (Internal Rate of Return), a metric that can be easily gamed.

Many GPs use subscription lines of credit (SLOCs) to delay calling LP capital, making IRR look higher than it actually is. This boosts the GP’s carry without necessarily improving the economic outcome for LPs.

📌 As an LP:

Don’t rely on IRR alone.

Ask how much return is driven by real company growth vs. financial engineering. Nothing wrong with the latter, but it comes with its own risks and works better in certain rate environments (ZIRP, the PE industry misses you)

Review how (and when) carry is calculated, and how subscription lines are used.

Preferred Return and the “Catch-Up” Clause

A preferred return, or hurdle rate, gives LPs a minimum return (often ~8%) before GPs start collecting carry. This structure is there to protect LPs, and it does, to a point.

The catch? Most funds include a GP catch-up clause, which allows the GP to rapidly collect backpay in carry after the hurdle is met. This can flatten the benefits of the preferred return, turning it into more of a timing mechanism than true downside protection.

📌 If you’re investing in a fund, read the catch-up provisions carefully. Some LPs prefer no catch-up or a partial catch-up structure to preserve alignment and protect downside.

This article was written by a securities attorney. It’s excellent:

Distribution Waterfalls: European vs. American

How profits flow to GPs and LPs is governed by the distribution waterfall—a key part of the fund’s Limited Partnership Agreement (LPA). There are two dominant structures:

➡️ European Waterfall (Whole Fund Model)

LPs get all their capital back

LPs get full preferred return

Only then does the GP earn carry

✅ LP-friendly

✅ Ensures the GP only gets paid after LPs are fully repaid

➡️ American Waterfall (Deal-by-Deal)

GP can collect carry after each successful deal

LPs may not yet be fully repaid or receive full preferred return

⚠️ Risk of misalignment: the GP can profit early, even if later deals underperform

📌 If a fund uses an American waterfall, LPs should insist on:

A strong clawback provision (to recoup excess carry if the fund underdelivers)

Possibly an escrow reserve for carry until the fund is fully wound down

Private equity is becoming more accessible, but that doesn’t mean it’s getting easier to evaluate. In Part 2, we’ll dive into the key risks and true drivers of returns, so you can separate marketing from material impact.

P.S. If you enjoyed this article, and know someone who will benefit from reading it, please share using the button below.