Understanding Unitranche Loans in Private Credit

“First-Out,” “Last-Out,” and why you should keep an eye on this structure

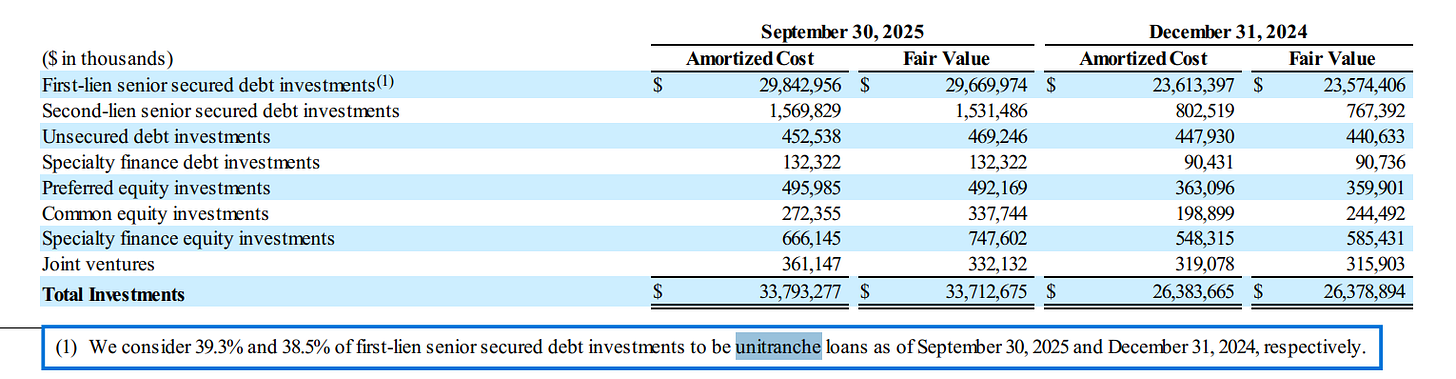

Some business development companies (BDCs) hold large concentrations of unitranche loans: ARCC’s portfolio is about 62%, while Goldman Sachs Middle Market Lending Corp. sits closer to 11.6%.

Some funds are refreshingly transparent:

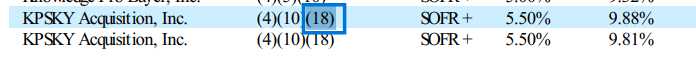

Others, however, make things far more challenging. Take the example below: this fund includes a small disclosure next to some loans in its schedule but doesn’t aggregate the total anywhere. (I fired up an LLM and aggregated the total for your enjoyment. It’s ~$4B).

See that reference to footnote 18? Here’s what it says:

”(18) These loans are“last-out” portions of loans. The“last-out” portion of the Company’s loan investment generally earns a higher interest rate than the“first-out” portion, and in exchange the“first-out” portion would generally receive priority with respect to payment principal, interest and any other amounts due thereunder over the“last-out” portion.” (Emphasis Leyla’s)

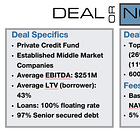

Speaking of BCRED, here’s a case study:

To be clear, “unitranche” is not the same as “last-out”. What % of BCRED’s loans are unitranche that are not last-out? Can’t tell.

What % of Blue Owl’s unitranche loans is last-out? Can’t tell.

In today’s guest post, Aznaur Midov breaks down what unitranche loans are, how they work, and why they matter for investors, focusing specifically on the “bifurcated unitranche” structure.

About the author

Aznaur Midov is the founder of KIÉR LIÓR, which manages co-invested private credit loan portfolios for institutional investors and family offices by combining expert underwriting with continuous borrower monitoring. He also writes Debt Serious, a weekly Substack newsletter that curates the most interesting news in private credit. He can be reached at aznaur.midov@kierlior.com.

👉 Invest in private credit? Start here:

Understanding Unitranche Loans in Private Credit

If you follow private credit, you’ve heard the term “unitranche loans,” but you may not be entirely sure what they are. According to the Corporate Finance Institute, a unitranche is a hybrid loan structure that combines senior and subordinated debt into a single debt instrument. That definition is fine as a starting point, but it doesn’t really help much in understanding how a unitranche works in practice.

To better understand it, let’s take a step back and look at how private credit typically fits into a leveraged buyout.

How a Unitranche Works

Suppose you are a private equity firm that wants to acquire a company for $700 million, which is a 14x multiple of its $50 million EBITDA. You plan to finance the acquisition with $300 million of equity and $400 million of debt.

👉 Invest in private equity? Read this:

Banks can provide cheaper financing, say SOFR + 3.75% to 4.00%, but they will probably only go up to $200 million (about 4x EBITDA), which is not enough.

Your remaining option is a standalone private credit loan (often called a “dollar-one” loan).

So, you call your friends at Orvantis Credit Partners to see what they can do. A few days later, you have the following conversation:

Orvantis: We spoke internally and can provide the entire $400 million you are asking for at SOFR + 5.75%.

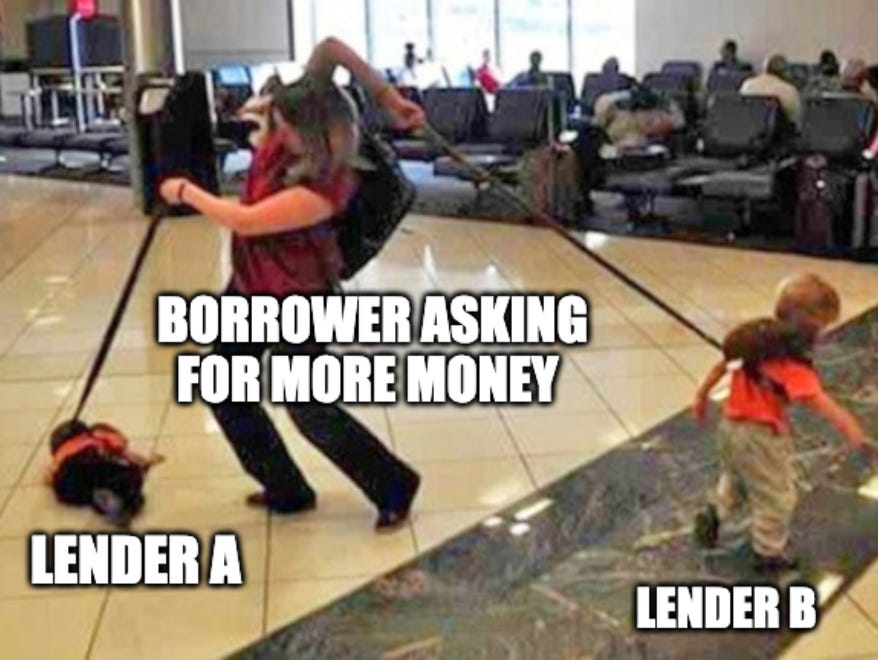

You: That’s a bit too costly. I was thinking more like SOFR + 5.00%.

Orvantis: We can’t go that low, but we can team up with Calvion Bank and offer a $400 million unitranche at SOFR + 5.25%. Calvion will be the First-Out lender, and Orvantis will be the Last-Out lender.

You: So, Calvion will be 1st lien, Orvantis 2nd lien, and we’ll have to negotiate two sets of credit agreements, two sets of covenants, pay for each lender’s counsel?

Orvantis: Nothing like that. To you, it’ll look and feel like a single 1st lien loan:

One credit agreement

One set of covenants

One lender counsel representing both Calvion and Orvantis

We and Calvion will have a separate agreement between us that spells out how we split economics, rights, and remedies. You don’t need to worry about that.

You: Interesting. Where’s the catch?